A KSN comrade and occasional Quaker explores the similarities and differences between the Kurdish Freedom Movement’s structures and those of the Quaker movement, in the hopes of highlighting a key UK ally in the struggle to bring about democratic modernity.

The Kurdish freedom movement often talks about the ‘two rivers’ of history: the river of Capitalist Modernity and the river of Democratic Modernity. The former refers to the history of state hegemony, capitalist realism and Darwinian competition that forms the only history most are ever exposed to, whilst the latter refers to the far older history of democratic society, communalism and mutual aid that predates it and has presented a continual resistance. The Kurdish movement identifies with this second current, but only as one example out of many.

As part of the movement’s call to build ‘world democratic confederalism’, it encourages everyone to learn the oft-suppressed democratic history of their own geographies. If we are to work towards democratic modernity within our own environs, we must be aware of this local history and build relationships with the democratic forces already hard at work all around us. This requires an ability to recognise such forces, beyond simply the words they use to describe themselves: every nation-state from the UK to the North Korea claims to be a democracy, and yet clearly they will be no allies in our struggle. How, then, can we recognise these truly democratic forces? How can we identify those who are making their own ‘cracks in the wall’?

A structural analysis can be helpful here. We can assume that a democratic organisation will empower its democratically-minded members to thrive within it, whilst also safeguarding against co-option by those less co-operatively inclined; therefore, we can expect there to be many similarities between the structures that work for such movements and those that don’t. However, even the points of difference may be informative, and help us to translate the ideas of the Kurdish movement into our own context.

In this article, then, I’d like to talk about one such organisation with a powerful presence in the democratic history of the UK (and beyond), and one whose structures have proved themselves resilient over several hundreds of years: the Religious Society of Friends, more commonly known as the Quakers. I won’t assume any prior familiarity with the Quakers, but some knowledge of the key ideas of the Kurdish freedom movement will be helpful. Also, I am talking here specifically about the ‘unprogrammed’ or ‘liberal/universalist’ Quakerism that is dominant in the UK, rather than the more evangelical form common in Africa and the Americas, with which I have no direct experience.

A Brief History of the Quakers

The Quakers (known formally as the ‘Religious Society of Friends’) originated as a Protestant Christian movement in the north of England in the mid-17th century, as part of the wider English Dissenter movement of religious radicalism following the English Civil War (along with both the Diggers and the Levellers). The early Quakers were marked by their belief that God was present within every person (and so there was no need for an ordained clergy), their refusal to swear oaths and the prominent role played by women. As one might imagine, the early Quakers faced sharp repression for many years, but nonetheless grew to a peak of around 60,000 members in 1680.

Membership shrunk in the 18th century as the movement became more inward-focussed and split repeatedly. Quakerism remained mainly evangelical until the so-called ‘Quaker Renaissance’ in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, which saw the movement (in the UK at least) shift towards a more liberal understanding of Christianity which continues to this day. It is this form of Quakerism that most people in the UK are familiar with, from their manning of ambulances in the First and Second World Wars to their regular (and often founding) presence in various protest movements, from anti-fracking and environmental direct action to tax resistance and anti-war mobilisations. Today there are a little under 12,000 active Quakers (and around 6,500 non-member attenders) in the UK, and around 400,000 Quakers worldwide.

Whilst Quakers do not have a fixed creed, they do collectively recognise a number of ‘testimonies’, which guide all Quaker faith and action. These testimonies are:

- Equality and justice;

- Peace;

- Truth and integrity; and

- Simplicity and sustainability.

Quaker Structures

The core unit of Quaker organising is the meeting. A ‘meeting’ can refer to both a group of Quakers assembled together for some shared purpose, and also the members of that group more generally, even when they are not physically together. There is no concept of holy ground in Quakerism, so a meeting can take place anywhere (often at protest sites). Some regular meetings are frequent, such as at weekly ‘meetings for worship’, whilst others are less so (e.g., the ‘Meeting for Sufferings’, who handle national affairs in-between Yearly Meetings and who meet five or six times a year). Other, specialised forms of meeting are organised as and when they are needed (e.g., ‘threshing meetings’).

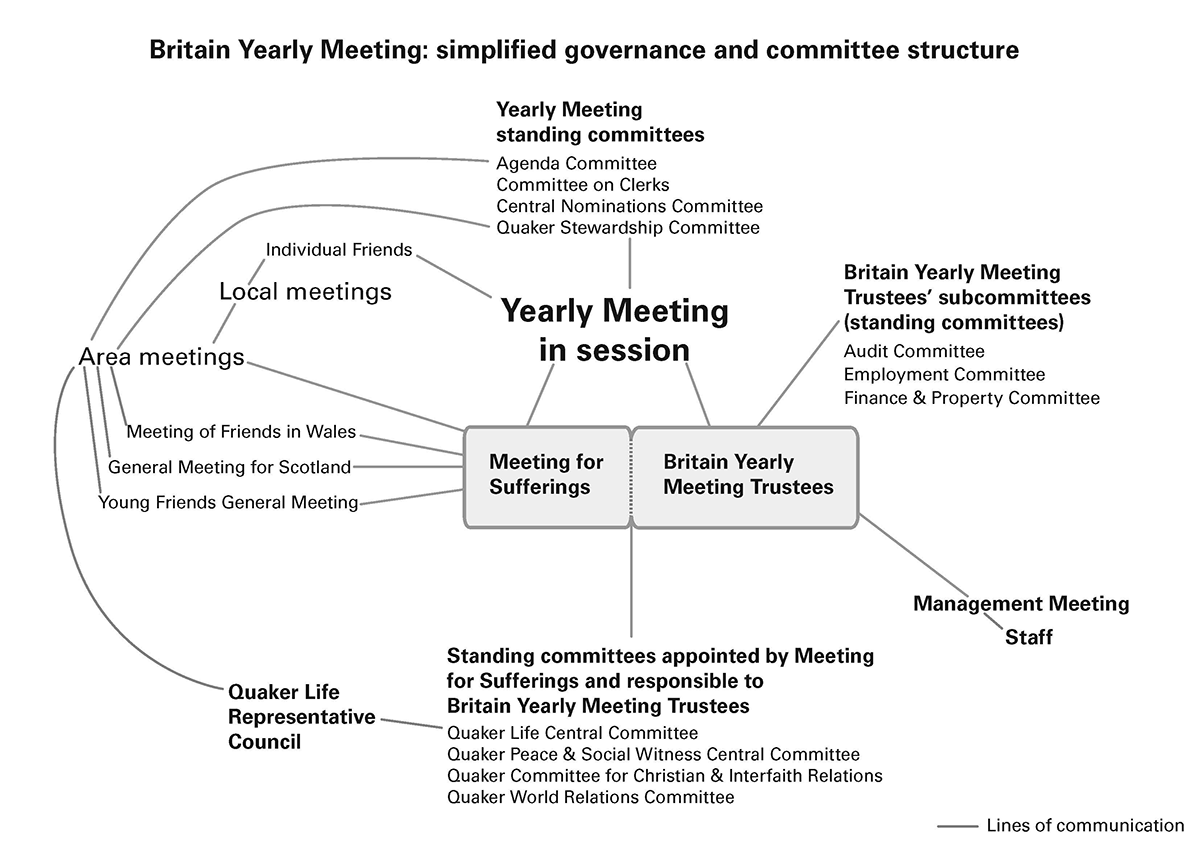

Quakers usually first join a ‘local meeting’ which covers a town or part of a city and meets regularly for shared worship and local administration. Local meetings are overseen by, and report to, an ‘area meeting’, which in turn form the ‘Yearly Meeting’—an annual assembly open to all card-carrying Quakers in the UK. Membership of the Society of Friends is not required to attend a local meeting, however, and ‘attenders’ are welcome to join on a one-off basis, or to attend for decades without ever joining the Society.

All of this is overseen by Britain Yearly Meeting (BYM), a registered charity which handles the oversight and implementation of decisions made by Yearly Meeting, area meetings and local meetings, in particular through several ‘standing committees’ which oversee work within a given area. BYM employs a number of staff, and all other appointments are made by nominating committees and may be ended at any time by the same body (or the appointee). On top of these meetings are other, more specialised groupings, such as the ‘Young Friends General Meeting’ of Quakers aged between 18–30, and there are many Quaker-formed and -supported groups spread throughout the world ranging from shared interest groups to schools and activist campaigns.

Similarities

There are, of course, some superficial similarities between the Quaker movement and the Kurdish freedom movement, from their use of the term ‘friend’ (or ‘heval’ in Kurdish) to refer to one another to their common focus on ecological sustainability as a core value. Both movements have also become more pluralist as time has passed; though they began as a Christian group and continue to use primarily Christian language in worship, Quakerism now is practised by people of all faiths and none, just as the Democratic Federation of Rojava was renamed the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria (AANES) to reflect the incorporation of Arab, Assyrian, Yazidi and other communities.

In addition, there are many overlaps in the histories of both movements. Both emerged during highly tumultuous periods—post-Civil War England and the political violence-riddled Turkey of the 1970s—and began with single charismatic leaders—George Fox and Abdullah Öcalan—and their supporters before developing into much more broad-base social movements. Both faced intense state repression at their outset, with both founders and many of their early followers facing regular imprisonment. Over very different timescales, both movements have also shown a remarkable capacity for ideological change since their foundings, whether in the Kurdish movement’s adoption of the New Paradigm in the 1990s or the Quaker Renaissance in the late 19th century.

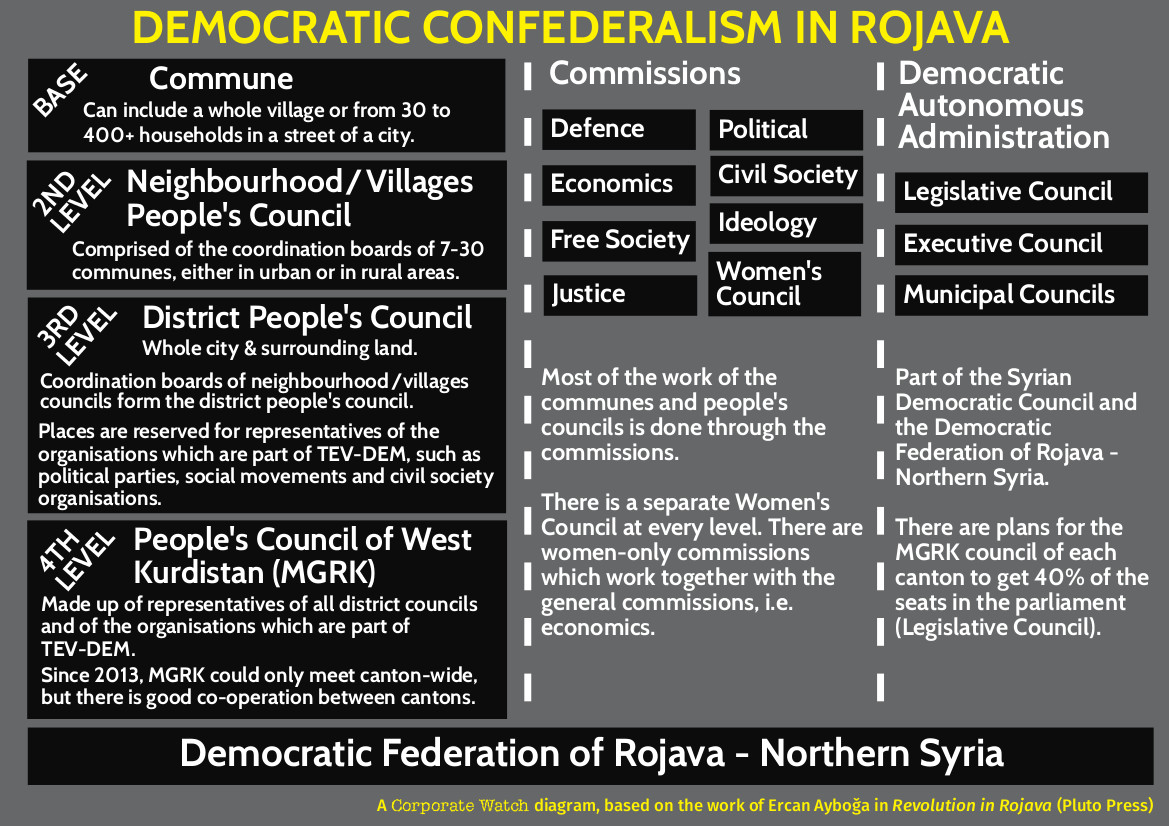

More interesting, I think, are the structural similiarities. I see many parallels between the Quaker system of meetings and committees and Kurdish model of democratic confederalism, both of which aim to guarantee subsidiarity by focussing on local groups (whether ‘meetings’ or ‘communes’) as the core organisational unit, whilst also structurally dissuading individualism in favour of collective action through cleverly-designed structures and mechanisms of accountability. Similarly, both rely on the establishment of adjacent structures (some short-lived, some longer-lasting) to focus attention on particular areas or issues, or to provide a space for members united by a common characteristic (such as youth). BYM plays a similar central co-ordinating role to something like TEV-DEM, with the staff employed to manage the day-to-day affairs of the Society paralleling the role of the xebatkar in Kurdish organisations.

Finally, the two appear to be in sync when it comes to perhaps the two most important aspects of any organisation: how it makes decisions, and how it deals with internal conflict.

In the former, Quakers are distinguished by the process of ‘Quaker decision-making’, in which a designated clerk is responsible for discerning, in the form of a minute, the ‘sense of the meeting’ once all present have had an opportunity to reflect and comment on the question at hand. This minute is then returned to the meeting to review, amend (if felt necessary) and eventually adopt, though it is crucial to note that this does not require unanimous support—only that all present agree that it accurately reflects the ‘sense of the meeting’. Similarly, Kurdish organisations aim to build consensus and have implemented various mechanisms to ensure that minority views are not lost amidst majority preference, such as quota systems.

Internal conflict, meanwhile, is dealt with in Quakerism through (you guessed it) more meetings. This may be a ‘meeting for clearness’, which originated as part of Quaker marriage preparation but has since been expanded to include ‘test[ing] a concern’, ‘seek[ing] guidance at times of change or difficulty’ and providing ‘help and comfort to the dying’, with the goal of enabling ‘those concerned [to] find a way forward’. This is only one option, however, and the Quakers are happy to highlight that ‘Friends were among the pioneers of conflict resolution as a distinct activity’; whether through mediation, counselling or ‘a quiet but firm reproof’, Quakerism has a rich toolbox of ways to defuse internal conflict and correct harmful behaviours, all taking place in the same spirit of mutual trust and a supportive community as tekmîl sessions within the KFM.

Differences?

However, none of this is to say that both movements are identical (nor would we expect them to be). They have both emerged from very different political situations, social milieus and cultural contexts and this necessarily has a deep impact on the resulting forms of each movement. However, I want to argue that what may at first appear to be irreconcilable differences may not be quite the obstacles they seem.

The first obstacle may well be what the Quakers are best known for: pacifism. How could the world’s oldest peace church possibly have anything in common with a movement that originated in a campaign of armed struggle against the Turkish state, and which continues that struggle in the various regions of Kurdistan today? I think that this comes from a misunderstanding of the Quaker peace testimony. In line with the Quaker position on all issues, exactly what this testimony entails is left to the discernment of each individual Quaker. This was seen in both the First and Second World Wars, where Quaker responses ranged from reluctantly joining the Armed Forces, to volunteering to serve in non-combatant roles, to strict conscientious objection (usually resulting in prison sentences, or worse).

Reinforcing this diversity of opinion, a section in Quaker Faith & Practice dedicated to highlighting the ‘dilemmas of the pacifist stand’ includes a 1661 quotation which could well be seen to echo Öcalan’s ‘rose theory’ of ‘legitimate self-defence’ when it states that ‘a great blessing will attend the sword where it is borne uprightly to that end and its use will be honourable’. In short, there are many different interpretations of just what this testimony requires from Quakers, and whilst many (perhaps even most) may take it to mean some form of pacifism, it is not necessarily as settled an issue as it may appear at first.

Another clear difference may be the role of women in both movements. Whilst both movements are distinguished by the number of women in positions of great influence throughout their histories—Magaret Fell could well be seen as a proto-Sakine Cansız for her role in documenting the activities of the early Quaker movement—the current state of affairs is very different. The Kurdish movement, through its separate women’s structures, quota system and male and female co-chairs, takes a more essentialist, separatist approach, whereas there is no contemporary parallel in Quakerism. However, it is worth noting that that has not always been the case; there were separate Women’s Meetings, both Yearly and local, throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, ending with the merging of the two Yearly Meetings in 1908 (though whilst they limited membership to women only, these did not have the same autonomy from the male-dominated general meetings as the Kurdish women’s structures today).

It is beyond the scope of this article (not to mention my personal experience) to compare integrative and separatist approaches to achieving women’s liberation, and the legal environment in the UK can perhaps make the latter more difficult to pursue. However, I will end by again highlighting the fluid nature of Quaker discernment and local group autonomy; groups are encouraged to experiment with new forms of organising such as co-chairs—to not be hindered from making experiments by fear or undue caution—and Quaker women (who made up some 58 % of members and attenders in 2021) have continued to organise independently in recent times, as they are led to do so.

The third, and perhaps most obvious, difference is that one movement faces existential threats on a daily basis, and the other does not. The Quakers do not maintain any independent territory; the Kurdish movement controls the liberated areas of north-east Syria. Quakers have never faced ethnic cleansing or genocide at the hands of either NATO militaries or Islamist terror cells; both are a daily reality for the Kurdish movement. The Quakers maintain an office at the UN; much of the Kurdish movement is internationally criminalised, and Öcalan remains imprisoned.

Obviously, these two movements operate in wildly different contexts, but I would suggest that this represents a good reason for us in the UK to study such local examples. The tactics, innovations and ideas that work for the Kurdish movement are unlikely to be exactly the same ones that work for our movements, and attempting to port them over directly is a recipe for disaster. But what could be more applicable to the British context than a movement still coming to grips with its complicated history of opposition to, and complicity in, the trans-Atlantic slave trade; a movement that can move successfully within liberal democratic spaces, even whilst stressing the supremacy of one’s conscience over the laws of states (#35); a movement that inculcates in its members effective techniques of mental self-defence against capitalist modernity (though without using either of those terms); and, last but by no means least, a movement that operates in English, rather than Kurdish?

Conclusion

This has been a somewhat surface-level, though hopefully also interesting, look at Quakerism through the lens of the Kurdish Freedom Movement. There are many more commonalities and differences that I could delve deeper into—I’ve just spent 2,700 words talking about a faith group without once touching on the topic of faith, for example—but in the interests of maintaining a manageable word count I will finish here.

In doing so, I want to return to my original objectives: to take some tentative steps towards identifying structural markers of a genuinely democratic organisation; to dig into apparent differences and argue that they can nonetheless be highly informative; and to provide a translation from the particular jargon of one movement to that of another, highlighting where the referents are the same whether we are talking about bringing about ‘democratic modernity’ or the ‘Kingdom of Heaven on earth’.

Quakers are by no means the only such example, nor even necessarily the best one, and I would enjoy reading similar comparative analyses of other movements I am less familiar with. However, if we wish to live in democratic modernity, we must learn how to fight for it in ways appropriate to our own contexts; as for where to start, how about talking to those who’ve been at it for 375 years?